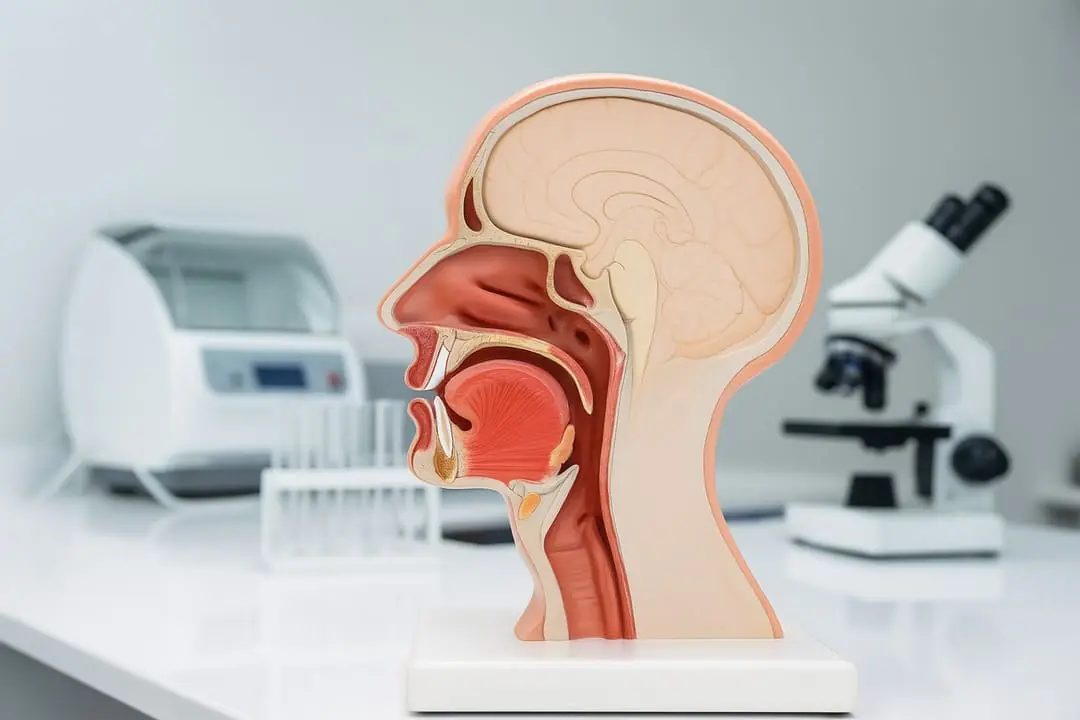

Although often overlooked, the role of the oral cavity in the digestive system is fundamental. It is not only the first point of contact between the body and food, but also the site where the initial physical, chemical, and sensory mechanisms of digestion are activated.

From chewing to saliva secretion and oral microbiome activity, the mouth initiates a complex chain of events that directly influences digestion, nutrient absorption, and even intestinal health. The function of the salivary glands goes far beyond simply hydrating and lubricating food—they also release key digestive enzymes such as salivary amylase, which begins carbohydrate digestion.

Furthermore, the eating experience is not limited to taste. The oral cavity is connected to other senses, such as smell, which plays an essential role in flavor perception through retronasal olfaction. These sensory pathways activate neural circuits related to pleasure and digestion, influencing digestive hormone secretion and preparing the body for nutrient processing.

In this way, digestion begins in the mouth long before food reaches the stomach.

Function of the Oral Cavity in the Digestive System

Digestion starts in the mouth, where physical and chemical processes prepare food for its passage through the digestive tract. This initial stage mainly involves mastication and salivation.

During mastication, food is mechanically broken down into smaller particles, increasing the surface area for digestive enzymes to act effectively. At the same time, saliva secreted by the salivary glands hydrates and lubricates the food bolus, facilitating swallowing.

Beyond mechanics, saliva initiates chemical digestion through enzymes such as salivary amylase and interacts with the oral microbiome, influencing the transformation and bioavailability of bioactive compounds.

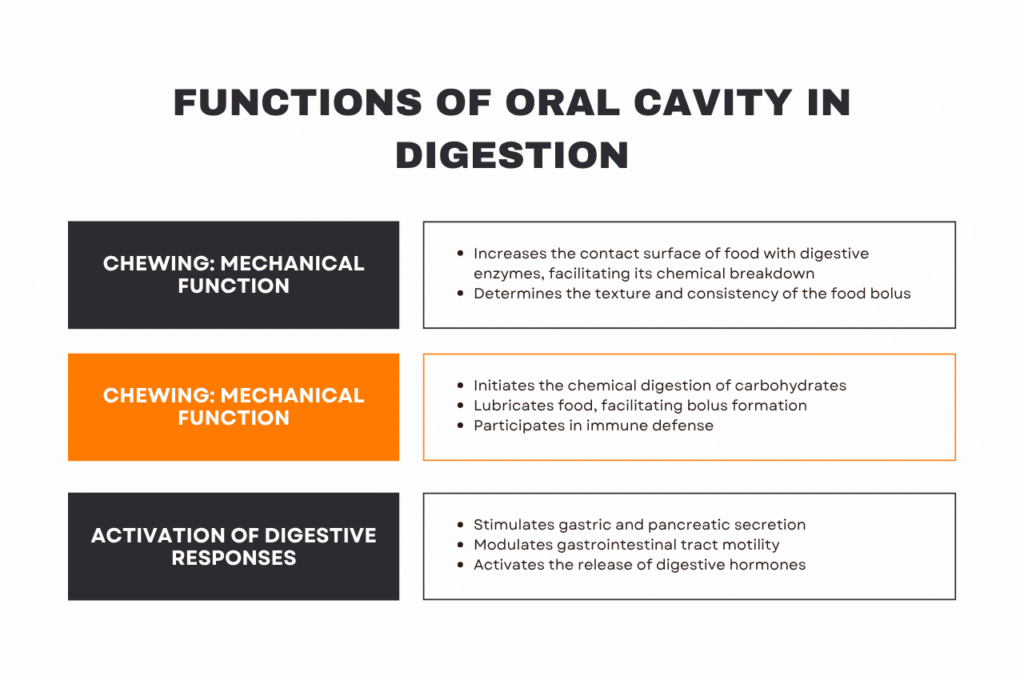

In summary, the oral cavity fulfills three essential functions:

- Mechanical: fragmentation and bolus formation

- Enzymatic: initiation of carbohydrate digestion

- Sensory: stimulation of digestive responses via taste and texture

These early processes strongly influence digestive efficiency and metabolic responses.

Mastication: Mechanical Function in Digestion

Mastication is the first active step in digestion. The coordinated action of teeth, tongue, and muscles breaks food into smaller particles, facilitating enzyme action and bolus formation.

Proper chewing improves gastric emptying and nutrient absorption, while poor mastication can impair later digestive stages.

Salivation: Chemical and Protective Function of Saliva

Saliva is a complex biological fluid composed of water, mucins, electrolytes, digestive enzymes, and antimicrobial compounds.

Its main roles in digestion include:

- Initial chemical digestion: salivary amylase breaks down starch into simpler sugars

- Lubrication: mucins facilitate swallowing

- Immune defense: lysozyme, lactoferrin, and IgA control pathogens

- Oral protection: pH regulation and enamel protection

Far from being a minor step, salivation strongly influences digestive health and microbiota balance.

To study these interactions more deeply, advanced cellular models are increasingly used, ranging from simple oral epithelial cultures and gingival models to complex systems like 3D bioprinted tissues and organ-on-chip devices. These technologies allow high-fidelity reproduction of the oral cavity’s microstructure and functionality, enabling the evaluation of immune responses, microbiota interaction, and the influence of saliva on initial digestion.

In the development of functional ingredients and nutraceutical products, it is increasingly common to use dynamic in vitro digesters that simulate the oral phase through to later stages such as intestinal digestion and colonic fermentation. These advanced systems make it possible to observe how compounds are transformed, what metabolites are generated in contact with the microbiota, and how they could exert systemic health benefits.

Salivary Glands: Types, Secretions, and Their Role in Digestion

The function of salivary glands in the digestive system is essential. Together, they produce up to 1.5 liters of saliva per day.

-

Parotid glands: secrete serous saliva, rich in digestive enzymes like amylase, which begins carbohydrate breakdown.

-

Submandibular and sublingual glands: produce a mix of serous and mucous saliva, aiding in lubrication and bolus formation.

-

Minor salivary glands: scattered throughout the oral mucosa, primarily secrete mucins that protect the mucosa and maintain moisture.

These secretions not only support initial digestion but also prepare food for passage through the digestive tract and protect the mouth from injuries and pathogens, contributing to both oral and overall health.

Function of the Salivary Glands: Sensory Activation of Digestive Responses

The oral cavity acts as a sensory control center. Taste, texture, and temperature signals activate reflexes that:

-

Stimulate gastric and pancreatic secretions.

-

Modulate gastrointestinal tract motility.

-

Trigger the release of digestive hormones.

The autonomic nervous system, via the gastrosalivary reflex, responds to these signals by anticipating the conditions needed for efficient digestion.

What Is the Role of the Oral Microbiome in Digestion?

The oral microbiome is composed of hundreds of microbial species that inhabit the teeth, tongue, gums, and mucous membranes. This complex ecosystem directly influences oral, immune, and digestive health.

Its main functions include:

-

Microbial competition against pathogens.

-

Stimulation of the local immune system (IgA, dendritic cells, lymphocytes).

-

Initiation of fermentation processes and modification of compounds in food.

-

Contribution to the balance of the gut microbiome, as some oral microorganisms survive the digestive transit.

Maintaining a balanced oral microbiome not only prevents periodontal diseases but may also have systemic implications, affecting intestinal and metabolic health.

The study of these complex interactions increasingly relies on advanced cellular models representing host–microbiome interactions. These include simple cell cultures like gingival cell lines, as well as more complex systems such as 3D bioprinted gum tissue, oral cavity models, and organ-on-chip devices. These technologies allow for a more realistic simulation of the oral microenvironment, facilitating the evaluation of immune responses, tissue barriers, and microbial dynamics.

In particular, for formulations that act from the earliest stages of digestion, dynamic digesters are increasingly combined with advanced cell models. This enables the controlled and physiologically relevant evaluation of how microbial and cellular interactions from the oral cavity to the colon can modulate the release and activity of bioactive compounds.